President Mubarrack & Former US Sec.Of State Andrew Cohen. Economic Espionage can be defined as calandestine methods used to undermine the economic and defense interests of a country.The damage from economic espionage can take the form of lost contracts, breach of contract, jobs and markets, and overall, withdrawal of committment by credit institutions and a diminished national competitive advantage. Uganda's current energy crisis is partly a consequence of economic sabotage. Tanzania's water and energy crisis also strongly point to potential calandestine acts of economic sabotage.Economic espionage obtains due to a clash in inter-state strategic economic as well as defense interests. This often is the work of intelligence services of state as well as formation of international alliances that undermine strategic enemy state action. In this thesis, I will explain the impact of Egypt's Strong Diplomatic footwork,her interest in the Nile and the Development process in Countries covered by the Nile.

President Mubarrack & Former US Sec.Of State Andrew Cohen. Economic Espionage can be defined as calandestine methods used to undermine the economic and defense interests of a country.The damage from economic espionage can take the form of lost contracts, breach of contract, jobs and markets, and overall, withdrawal of committment by credit institutions and a diminished national competitive advantage. Uganda's current energy crisis is partly a consequence of economic sabotage. Tanzania's water and energy crisis also strongly point to potential calandestine acts of economic sabotage.Economic espionage obtains due to a clash in inter-state strategic economic as well as defense interests. This often is the work of intelligence services of state as well as formation of international alliances that undermine strategic enemy state action. In this thesis, I will explain the impact of Egypt's Strong Diplomatic footwork,her interest in the Nile and the Development process in Countries covered by the Nile.A battle for control over the Nile has been raging out between Egypt, which regards the world's longest river as its lifeblood, and the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, which complain that they are denied a fair share of its water.In the latest escalation in the dispute, which some observers believe could lead to a new conflict in east Africa, Tanzania has announced plans to build a 105-mile pipeline drawing water from Lake Victoria, which feeds the Nile. The project "flouts" a treaty giving Egypt a right of veto over any work which might threaten the flow of the river.

The Nile Water Agreement of 1929, granting Egypt the lion's share of the Nile waters, has been criticised by east African countries as a colonial relic. Under the treaty, Egypt is guaranteed access to 55.5bn cubic metres of water, out of a total of 84bn cubic metres. The Egyptian water minister, Mahmoud Abu-Zeid, recently described Kenya's intention to withdraw from the agreement as an "act of war". Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the former secretary-general of the UN, has predicted that the next war in the region will be over water.

The Nile Waters Agreement (NWA) over the allocation of its waters between Egypt and Great Britain (which represented Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika [now Tanzania] and the Sudan) was concluded on November 7, 1929 in Cairo by an exchange of letters between the Egyptian Prime Minister and the British High Commissioner in Egypt. The agreement allocated 48 billion cubic meters per year to Egypt as its acquired right and 4 billion cubic meters per year to the Sudan.

These allocations were later increased to 55.5 billion cu. meters and 18 billion cu., respectively, under a 1959 bilateral agreement between these two countries that allowed for the construction of the Aswan Dam. Apart from Ethiopia, which had a government in place, the NWA was made before the other Nile Basin countries gained their independence.

These allocations were later increased to 55.5 billion cu. meters and 18 billion cu., respectively, under a 1959 bilateral agreement between these two countries that allowed for the construction of the Aswan Dam. Apart from Ethiopia, which had a government in place, the NWA was made before the other Nile Basin countries gained their independence.  The agreement stated that no works would be undertaken on the Nile, its tributaries, and the Lake Basin that would reduce the volume of the water reaching Egypt. It also gave Egypt the right to "inspect and investigate" the whole length of the Nile to the remote sources of its tributaries in the Basin.

The agreement stated that no works would be undertaken on the Nile, its tributaries, and the Lake Basin that would reduce the volume of the water reaching Egypt. It also gave Egypt the right to "inspect and investigate" the whole length of the Nile to the remote sources of its tributaries in the Basin.  This right "to inspect and investigate," which was tantamount to a veto power over any water or power project, has in recent years become moot, as all the former colonies on the Nile Basin have become independent nations and are not likely to readily agree to such encroachment on their sovereignty by Egypt. Indeed, some of them have begun to nibble on the NWA by initiating water projects that threaten to reduce the volume of water available to Egypt. Egypt considers any change in the agreement as a strategic threat and has repeatedly threatened to use all means at its disposal to prevent the violations of the agreement.

This right "to inspect and investigate," which was tantamount to a veto power over any water or power project, has in recent years become moot, as all the former colonies on the Nile Basin have become independent nations and are not likely to readily agree to such encroachment on their sovereignty by Egypt. Indeed, some of them have begun to nibble on the NWA by initiating water projects that threaten to reduce the volume of water available to Egypt. Egypt considers any change in the agreement as a strategic threat and has repeatedly threatened to use all means at its disposal to prevent the violations of the agreement. The other Nile Basin African countries consider the agreement as a relic of a colonial era which no longer reflects their needs and aspirations and hence it should be annulled. Countering this argument, Sherif Al-Mousa, head of the Middle East Program at the American University in Cairo, argues that the Nile water agreement should be treated the same way as the boundaries of most Nile Basin countries which were established by colonial powers, and are recognized under international law.This has been gravely resented by east African countries since they won their independence. Kenya and Tanzania suffer recurrent droughts caused by inadequate rainfall, deforestation and soil erosion. The proposed Lake Victoria pipeline is expected to benefit more than 400,000 people in towns and villages in the arid north-west of Tanzania.

The other Nile Basin African countries consider the agreement as a relic of a colonial era which no longer reflects their needs and aspirations and hence it should be annulled. Countering this argument, Sherif Al-Mousa, head of the Middle East Program at the American University in Cairo, argues that the Nile water agreement should be treated the same way as the boundaries of most Nile Basin countries which were established by colonial powers, and are recognized under international law.This has been gravely resented by east African countries since they won their independence. Kenya and Tanzania suffer recurrent droughts caused by inadequate rainfall, deforestation and soil erosion. The proposed Lake Victoria pipeline is expected to benefit more than 400,000 people in towns and villages in the arid north-west of Tanzania.

Tanzania Challenges Egypt

In early February 2004, Tanzania launched a project to draw water from Lake Victoria to supply the Shinyanga region. The project calls for the construction of about a 100 mile long inland pipeline at an initial cost of $27.6 million, to be constructed by a Chinese engineering company. To mitigate the anticipated Egyptian reaction, Tanzania announced that the pipleline was designed to provide drinking water to its thirsty population rather than irrigate agricultural land.

Tanzania's population of 35 million has suffered from frequent droughts, desertification, and soil erosion. In fact, Tanzania was the first riparian country which, upon its independence in 1961, declared the 1929 agreement invalid.

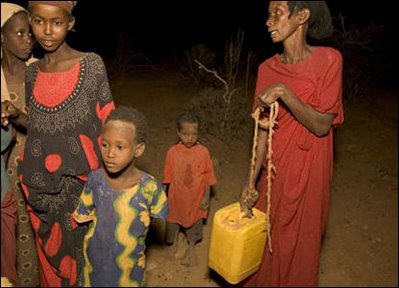

"These are people with no water," said the Tanzanian wa

ter minister, Edward Lowasa. "How can we do nothing when we have this lake just sitting there?"

ter minister, Edward Lowasa. "How can we do nothing when we have this lake just sitting there?" Suzanne Mubarak & Laura Bush.

Suzanne Mubarak & Laura Bush.Another Challenge from Kenya

Similarly, in response to a threat from Kenya that it was considering withdrawing from the 1929 agreement, the Egyptian Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources Mahmoud Abu Zeid said: "Egypt considers the withdrawal of Kenya from this agreement as tantamount to official declaration of war and a threat to its vital interests and national security." A Kenyan weekly quoted the Egyptian minister declaring in Addis Ababa that Kenya could be subject to sanctions by Egypt and the other eight members of the Nile River Basin Agreement. He said Kenya's position violates international law and customs "and we will not agree to it."

The Kenyan deputy foreign minister M. Watangola repeated his country's demand for a revision of this historic agreement because Kenya was not consulted prior to its being signed. He said eight Kenyan rivers flow into Lake Victoria, which is the main source of the Nile waters.

The Kenyan deputy foreign minister M. Watangola repeated his country's demand for a revision of this historic agreement because Kenya was not consulted prior to its being signed. He said eight Kenyan rivers flow into Lake Victoria, which is the main source of the Nile waters.

Ethiopia Asserts Rights to the Blue Nile

The Ethiopian Minister of Water Resources announced his country's intentions to develop close to 200,000 hectares (ha.) of land though irrigation projects and construction of two dams in the Blue Nile Sub-basin. He further stated that these projects would be the first phase of forty-six projects which Ethiopia proposed to execute along with ten joint projects which Egypt and Sudan proposed.

The Ethiopian Minister of Water Resources retorted that the agreement to participate in the Nile Basin Initiative reserves Ethiopia's right to implement any project in the Blue Nile Sub-basin unilaterally, at any given time. He charged that the 1959 agreement between Egypt and Sudan impedes sustainable development in the basin and called for its nullification.

The Ethiopian Minister of Water Resources retorted that the agreement to participate in the Nile Basin Initiative reserves Ethiopia's right to implement any project in the Blue Nile Sub-basin unilaterally, at any given time. He charged that the 1959 agreement between Egypt and Sudan impedes sustainable development in the basin and called for its nullification.A Ugandan commentator Charles Onyango-Obbo wrote sometime back: "Egypt can't enjoy the benefits of having access to the sea, while blocking a landlocked country like Uganda from profiting from the fact that it sits at the source of the Nile." Uganda seems the least engaged in this battle for lack of diplomatic muscle, a visible lack of capacity for the state to initiate large projects and therefore has not given any direct threat to Cairo. Uganda's other disadvantage is also the role of IMF/World Bank whose influence in the running of the economy is enormous through budget support. Egyptian Intelligence also has classified the Ugandan state as unable to pose an immediate strategic threat and therefore contained.This means Egypt does not need to use threats of military action when it can diplomatically sabotage the development of strategic interests of Uganda through her sole source of direct financing. It is different with Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania countries that have moved fast to bring on the Chinese growing global influence in strategic investments. Uganda is still waiting in the wings because of her two decade alignment with the West. The state in Uganda has not made a bold step to bring on board the Chinese government growing economic muscle in her foreign policy because her multi-lateral and bilteral donors are mainly from Western Europe. Problem is Egypt is strongly allied to the US & Britain on mutual long term interests.The governments above are in a way directly involved in the economy through public interventions meaning they can finance big projects thus Egypt's tough response. Uganda is another case. Only the government can ponder about its state resignation at this glaring economic espoinage by Egypt and the donor community and re-align its foreign policy to address development contraditions.

Through economic espionage, Egypt potentially is stiffling social-economic development because of her diplomatic foot work in Washington and London. It means, leaving strategic investments to private investors can be sabotaged through financial incetives by state as well as withdrawal of financing committments by International Credit Institutions with a more aggressive establishment in Cairo. Uganda technically is a victim of this to the greatest disadvantage as state planners wait for IMF/World Bank Instructions.In otherwords, we have to raise the bar of diplomatic engagement as well start looking at our mandate critically as a state like Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania have done.

Through economic espionage, Egypt potentially is stiffling social-economic development because of her diplomatic foot work in Washington and London. It means, leaving strategic investments to private investors can be sabotaged through financial incetives by state as well as withdrawal of financing committments by International Credit Institutions with a more aggressive establishment in Cairo. Uganda technically is a victim of this to the greatest disadvantage as state planners wait for IMF/World Bank Instructions.In otherwords, we have to raise the bar of diplomatic engagement as well start looking at our mandate critically as a state like Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania have done.

While east African countries are eager to make greater use of the river, Egypt fears any threat to its lifeblood. Most of Egypt's population lives in the Nile valley - on 4% of the country's land - and any fall in the water level could be disastrous. From the Egyptian perspective, any change in the volume of its water could have devastating effects on Egypt. The vast majority of Egyptians live in a valley which is about 4 percent of the Egyptian territory, and 95 percent of Egypt's water resources are derived from the Nile.

Nevertheless, Egypt expressed its irritation with any project, arguing that under the 1929 agreement it has the right to veto any project - agricultural, industrial, or power - that could threaten its vital interests in guaranteeing its annual share of the river waters. While Egypt is handling the issue diplomatically, Egyptian officials stressed that "the diplomatic dialogue does not mean that Cairo does not consider any number of other options, if necessary." In diplomatic parlance, "other options" do not exclude the use of force. Tanzania has not budged. The Deputy Permanent Secretary in the Tanzanian Ministry of Water and Livestock Development, Dr. C. Nyamurunda, said that Tanzania's sentiments about the legality of the water agreement are well known. He emphasized that "other countries also believe that the treaties [NWA] were illegal but they are to cooperate in negotiations, although they are not restricted from using the waters of the Nile."

An estimated 160 million people in 10 countries depend on the river and its tributaries for their livelihoods. Within the next 25 years, the population in the Nile basin is expected to double, and there is a growing demand to harness the river for agricultural and industrial development.

ADiplomacy

The Nile treaty was drawn up at a time when Egypt was a British satellite, regarded as strategically crucial by London because of the Suez canal, which controlled access to India. The agreement is now in effect enforced by international donors, who are reluctant to advance funds for major river projects that will upset Egypt, a key Arab ally of the US in the Middle East.Sub-Saharan countries cannot match Egypt's diplomatic clout, but they face a dilemma as a major untapped resource rolls through their territories.

"We have reached a stage where all the Nile basin countries are confronted by domestic development challenges," said Halifa Drammeh, a deputy director of the United Nations environment programme. "How many people have access to safe water? How many have access to sanitation? There is a tremendous pressure on these governments to sustain the needs of their populations, and to raise their standard of living.

"After all, there is nothing we can do in life without water. Wherever there is sharing, there is potential for conflict."

The Nile is shared by ten countries – Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda –- with a combined population of about 300 million, about 160 million of whom live within the boundaries of the Nile Basin. The ten countries that share the Nile waters include some of the world's poorest, with annual per capital income of less than $250.

The Pressures for Change

Population pressures, frequent draughts, and increasing soil salinity have intensified the demands by the Nile Basin countries to renegotiate the 1929 agreement. Not deterred by Egyptian reluctance to negotiate the 1929 agreement, or even Egyptian threats, and constrained by financial hardships, some Nile Basin countries are determined to implement projects that would tap into the sources of the Nile.

The Nile Basin Initiative notwithstanding, member countries are forging ahead with their own projects and challenges. Droughts are difficult to forecast, even in the beginning of the crop season. Building dams to store water is not unlike a bank savings account, to be used at a time of need. While Egypt has secured its agriculture with the building of the Aswan Dam, it has been reluctant, if not belligerent, when other countries on the Nile Basin sought similar solutions.

The Nile Basin Initiative notwithstanding, member countries are forging ahead with their own projects and challenges. Droughts are difficult to forecast, even in the beginning of the crop season. Building dams to store water is not unlike a bank savings account, to be used at a time of need. While Egypt has secured its agriculture with the building of the Aswan Dam, it has been reluctant, if not belligerent, when other countries on the Nile Basin sought similar solutions.Water for Oil

A senior Kenyan parliamentarian suggested that the Nile water should be sold to Egypt and Sudan for oil. He said that the time has come to replace the Nile agreement with a new agreement to allow the members to benefit from the Nile's waters. He added: "We have presented our natural resources to Egypt and Sudan free without them doing anything in return. We need to sell to them as they sell to us." The Egyptian treated the idea as "stupid" because the two countries have vested rights, rather than customers who would buy the water.

Egypt Accuses Hidden Fingers

In addition to Tanzania and Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda are also demanding the abrogation of the 1929 agreement and a bigger share of the Nile waters. Egypt accuses "hidden fingers known to the Egyptian side [which] are openly inciting the traditional allies of Egypt in the Nile Basin to annul the agreement, arguing that it is incompatible with the population and political developments that have transpired in the last 75 years." The anonymous senior Egyptian official who has made the allegation about the "hidden fingers" stressed that any change in the agreement was inconceivable and warned that "any infringement of the agreement would suggest that the African countries do not respect regional obligations."

Egypt's Alternatives

To deal with the threat to its vital oil supply Egypt has four alternatives. Some are not mutually exclusive:

· Reduce waste through improved irrigation system.

· Price water at market rates.

· Maintain the status quo as long as feasible.

· Resort to the use of force.

Reduce Waste Through Improved Irrigation System

According to a study by the World Bank, 96.44 per cent of the economically active population in Egypt is engaged in agriculture. It is the highest percentage in the Middle East, with Morocco in second place with 92.61 percent of active population in agriculture. By contrast, the corresponding ratios for Tunisia and Lebanon are 60.87 and 10.35 percent, respectively. As a result, much of the water is used in agriculture, which contributes proportionately a small percentage to GDP. In Egypt, 88% of the water is consumed in agriculture which, as a sector, contributes only 14 percent to GDP, while 8 percent of water used in industry contributes 34 per cent of GDP. The report suggests that "from a narrow macroeconomic perspective, rationale of justifying the allocation of water to agriculture over industrial and other sectors is weak."

Price Water at Market Rates

While the region remains one of the most water-scarce regions in the world, the cost of water for irrigation is set at below cost recovery levels. Egyptian agriculture is entirely dependent on irrigated land. The government provides irrigation water free, except of cost recovery of on-farm investment projects. Annual irrigation subsidies are estimated at $5 billion. In Egypt, irrigation subsidies are often rationalized as a means of offsetting low farm prices controlled to keep down urban food prices.Water pricing and subsidies are such that they lead to waste in agriculture and provide little incentive for conservation techniques.

Maintain the Status Quo

Egypt's third option is to seek a status quo while tolerating some changes on the margin. To do so, Egypt must continue to maintain a pro-American and pro-Western orientation to discourage them and organizations controlled by them, such as the World Bank, from financing costly water projects such as dams or power projects in any of the riparian countries, which they themselves cannot finance through internally-generated resources.

Resort to the Use of Force

The last and least likely alternative is to resort to the use of force to uphold Egypt's right to exercise the veto power on activities that it deems dangerous to its national interests. Egypt's saber rattling cannot be taken too seriously, certainly not by the African countries themselves. Indeed, as one Egypt daily pointed out, "the harsh language adopted by Abou Zeid … might not be working…" Not only does Egypt lack the military capacity to strike at countries two thousand miles outside its borders, but it will be hard pressed to justify a military action to enforce the provision of a 75-year old agreement concluded to satisfy colonialist considerations and priorities but dissatisfy the needs of the countries upstream. A Kenyan father of two, who owns eight ponds for fish farming, was quoted as saying: "If the Egyptians try to invade Kenya for the sake of its water we are ready to die for our rights. Kenya must forget the Nile agreement and return to the commercial consumption of the Lake Victoria Lake."